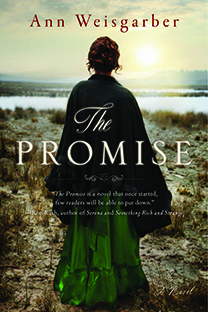

Inside the Book

Excerpt from The Promise

Prologue – The Vigil

Prologue – The Vigil

October 1899

There wasn’t nothing good about funerals. The very notion of them was a disturbance. I’ve told my kin, when my time comes, don’t lay me out for people to look at. Just close the coffin and bury me quick. But these Catholics had other notions. They stretched a funeral like nobody else could.

That was how it was for Bernadette. She was laid out in the middle of her parlor with three sawhorses holding up the coffin. It was the second day of October, still full daylight and plenty warm, but Sister Camillus had lit three white candles. They were on a tall metal stand near the foot of the coffin. At the other end, a stand held a crucifix. That was what they called it. A crucifix. I didn’t like it, Jesus wearing a crown of thorns, His hands and feet nailed to the cross, and His bare ribs showing. It wasn’t seemly. I wished someone would move that thing but nobody did.

A few hours before the vigil started, the neighbors showed up in their wagons. That set the dogs barking, and my two brothers had to go out and herd them into the barn. The neighbors came from up and down Galveston Island, and they came wearing black. The women were in their mourning dresses with their corsets pulled extra tight for the occasion. I’d done the same. The men wore suits and their white collars were starched to stand up even when they took to tugging at them, sweat dribbling down the sides of their faces.

The neighbor women brought baskets of food filled with platters of shrimp and oysters. They brought pans of cornbread, bowls of purple-hull peas, and more cakes than I had room for on Bernadette’s kitchen table. They talked in low tones – ‘Ain’t it sad?’ ‘Don’t it break your heart?’ – the feathers on their hats bobbing as we put out the food. It was supper time but nobody ate. It didn’t seem right with Oscar standing by the coffin, his green eyes dulled with sorrow. There was no getting away from seeing him, the kitchen being the other half of the front room. Couldn’t keep from seeing the neighbor men, either, them clumped around Oscar. They turned their hats in their hands as they mumbled condolences; Daddy kept pinching the crown in his. My brothers weren’t much better but the married men were the most skittish. Their gazes skipped around until they found their wives. Don’t die, I could see the men think. Don’t leave me with our little ones, me not knowing what to do, me having to give them away or remarry quick. Don’t let me be like Oscar, widowed with a four-year-old boy.

It was hurtful to watch.

It didn’t take long for the men to drift away from Oscar and go out to the front veranda. That was where the neighbor children were. The boys sat on the wide-planked floor with their black-stocking legs poked between the railing posts so that their feet could dangle and swing. The little girls sat on the steps that led up to the veranda, their hair in braids and tied with ribbons. I saw them from the front kitchen windows, and I didn’t blame the men and the children for staying outside. There, the breeze whisked away the sweat. Outside, they could look at the sky with its high-riding puffed clouds. The house sat up on five-foot-high stilts and from the veranda, a person could see the rows of tall sand hills that were a quarter of a mile from the front of Bernadette and Oscar’s house. The Gulf of Mexico was on the other side of the sand hills and far off, at the horizon, a trail of steamships and schooners waited to come into Galveston’s port.

On the veranda, the neighbor men shucked off their high collars and went to the dairy barn, some of them taking their children with them. At the barn, I figured the men did what came natural. They worked. They filled the water troughs, and they cleaned out the stalls. They worked so that Oscar wouldn’t worry overly about his milk cows.

Likely Oscar wasn’t thinking about nothing else but Bernadette. As Mama said, he wasn’t but a shadow of himself since she took sick a week ago.

When the vigil started, the Baptists mostly left and went on home. I wanted to do the same, I wanted to breathe air that wasn’t filled up with sadness. But Bernadette had been my friend since she and Oscar got married, and a person didn’t run out on friends.

Neither would I run out on Oscar.