Book Talk

My Hurricane Experience

In 2012, three days before Hurricane Sandy struck New Jersey, I e-mailed friends in the area. Charge your cell phones, I wrote. Get cash. Make sure you have gas in your cars. Move your cars to the upper floors of a parking garage. Fill every container you own with water. Pack the freezer section of your refrigerator with ice. Buy a generator, if you can find one.

They wrote back with one question. Why?

Because if the power goes out, it could be days, weeks, even months before it’s restored. Charge card services, banks, and gas stations can’t operate. If the streets flood, so will your car. If the water pumping stations flood, drinking water will contaminated. If your refrigerator isn’t working, ice will keep it cool for a few days. And if you have a generator, you can plug in your laptop and get the latest news. Or maybe plug in a lamp. It’s surprising what a difference one lamp can make after the sun has set.

It did for me when our last hurricane, Ike, hit the Galveston/Houston area on September 13, 2008.

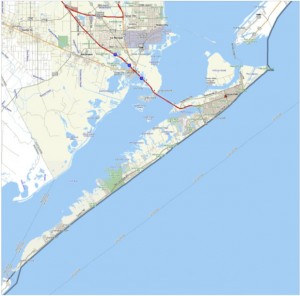

At the time, I lived in Sugar Land, Texas, about seventy miles inland from the Gulf of Mexico, and had a beach house on Galveston Island where my husband, Rob, and I spent weekends. For seven days before Ike struck land, we followed news updates about the track of the storm. It could come ashore at New Orleans to our east, we were told. Or it could make landfall farther down the Texas coast. The best guess, though, was Galveston.

We knew what that could mean. A few years before, Katrina had devastated New Orleans. A handful of weeks after Katrina, Beaumont, Texas, was slammed by Rita. Now Ike was on its way. At the beach house, we brought in deck furniture, took pictures down off the walls, rolled up rugs, emptied the refrigerator, turned off the electricity, and shut off our supply of water. We secured the storm shutters, said goodbye to the house, and left Galveston.

Two days before the storm was expected to make landfall, the Galveston mayor called for a mandatory evacuation. People in low-lying areas close to Houston also evacuated. In our Sugar Land home, we watched television footage of waves crashing over Galveston’s seawall, seventeen feet above the beach. Twelve hours before landfall, tides from the bay and the gulf began to flood the streets of Galveston. People who had intended to evacuate but had waited too long were trapped.

Two days before the storm was expected to make landfall, the Galveston mayor called for a mandatory evacuation. People in low-lying areas close to Houston also evacuated. In our Sugar Land home, we watched television footage of waves crashing over Galveston’s seawall, seventeen feet above the beach. Twelve hours before landfall, tides from the bay and the gulf began to flood the streets of Galveston. People who had intended to evacuate but had waited too long were trapped.

We rode out the storm in our Sugar Land house, and it was frightening. The electricity went out early, and we lost telephone and Internet service. We relied on a hand-cranked radio for news. The air hummed, the oak trees bowed and swayed, and our windows shook, about to blow out. Our house is by a creek and in my mind’s eye, I was sure that the alligators had crawled up the banks in search of high ground.

It was a long night. When the storm passed, our house had roof damage and water came under the house and ruined the wood floors, but we were fine. The electricity still down, we fired up our generator so we could alternate between running the refrigerator and turning on a lamp. Our attention then turned to Galveston and to neighboring Bolivar Island.

For a day, there was little news. The National Guard, the Coast Guard, and police from all over the country arrived to rescue people who were trapped by the storm and to protect the island from looters. Television crews were not allowed on the island and we later learned that government officials were afraid there had been many deaths. Eventually, aerial photos of the island were broadcast. Almost every home on Bolivar Island had disappeared but Galveston was far more fortunate. About twenty people had died and some sixty were missing but this was less than expected.

Seven days after the storm, city officials made the unexpected announcement that people could return to the island for a few hours during daylight to check on private property. Rob left work and made a beeline for Galveston. It was slow going.

Sailboats and shrimp boats had washed up onto the causeway that linked the island to the mainland.

Once on the island, Rob had to pass through police checkpoints where his identity was checked and rechecked. Sand was several feet deep on the roads, and bulldozers had cleared narrow paths so cars could pass through one at a time. In the downtown area, buildings and Victorian-era homes had up to eight feet of saltwater inside of them. Mud and dirt coated their exterior walls.

The island was littered with broken staircases, furniture, flooded cars, refrigerators, and mattresses. Rope and fishing lines seemed to be tangled in every bush. Electricity was out, and there was no running water since the pumping stations had flooded.

Our beach house is on seventeen-foot high pilings and was intact. The metal storm shutter that protected our front door was still locked and secured, but when Rob opened the shutter, the front door stood wide open. This was a shock since we had locked it with the deadbolt when we were last at the house. Apparently, the house had swayed so much that the bolt slipped loose. There was also evidence that a coyote had ridden out the storm on the deck.

Across the street and on the beach, a house had collapsed and another one disappeared, leaving only the broken pilings. Along the bay, the wind had punched holes in the homes and tore off parts of roofs.

Rob left and a few days later, he and I went to Galveston to shovel the thick gooey sand and mud that was under the house and on the driveway. There were also mounds of debris to pick up. Golf clubs, rowboats, boards from destroyed decks, picnic tables, chairs, canned food, dishes, and toys had washed up from other houses.

We brought our own drinking water and a cooler packed with food since there were still no services. We had had tetanus shots – rusty nails were everywhere – and wore boots and long pants in spite of the boiling heat. We had been warned about rattlesnakes that were stirred up after the trauma of the storm. The island hospital was closed and if bitten, it would take about an hour and half to get to the closest hospital. “Good luck,” my doctor’s nurse had said when I’d asked what we should do if either of us was bitten by a snake.

It was about a month before electricity and water services were restored. Some businesses were able to open quickly while others took several years. People whose homes were inhabitable lived in small trailers for up to two years. Disputes over insurance claims delayed the rebuilding efforts. Some people left, even those who had lived all their lives in Galveston. But many stayed, determined to start again. That was a decade ago, and we still measure time as before and after Ike.

It was about a month before electricity and water services were restored. Some businesses were able to open quickly while others took several years. People whose homes were inhabitable lived in small trailers for up to two years. Disputes over insurance claims delayed the rebuilding efforts. Some people left, even those who had lived all their lives in Galveston. But many stayed, determined to start again. That was a decade ago, and we still measure time as before and after Ike.

I now live in Galveston. Like many of us who live near the Gulf, I understand the force of hurricanes and know there will be more. But this is home, and we’ve weathered hurricanes before. We know what to do. We roll up the rugs, move inland, and hunker down.

More Writings